5 Categories of AI Coding Agent Mistakes

I’ve been using AI coding agents heavily for nearly two years. I started keeping a list of the dumb things they do… sometimes just weird things, sometimes things where I had to go in and fix, and sometimes just annoying things I’d have to tell the agent over and over to fix.

The list got long. This isn’t everything, but it’s representative. If you’ve been building with AI, I’m sure these will feel familiar:

- Imports in the middle of code

- Repeated implementations all over the place

- DB migrations in a class initialization (?? crazy)

- Writing raw SQL when the project uses an ORM

- Notional or placeholder data

- Notional or placeholder implementations

- Useless comments:

- Using browser alerts in web apps

- Using raw/manual access when the framework offers ways to do things (i.e. window.location instead of React Router)

- Changing unrelated code when working on a feature

- Creates helper methods then doesn’t use them

- Creates types for everything (…then doesn�at’s responsible for a zillion things so it’s hard to debug or test

- Putting sensitive secrets into client side code

- Putting sensitive secrets into client side code

- Redeclaring variables all over the place

- “Any” is everywhere

- Inline objects and functions instead of reusable stuff

- Creates (and tries to commit) test scripts

- Unused imports and dependencies

- Ignoring reusable project components

- Complex fallback strategies instead of just… robust code

- Comments out problematic stuff with a “come back later” note

- Adds feature flags for everything

- Adds flags, variables, and parameters all over the place …

TL;DR (as usual :) )

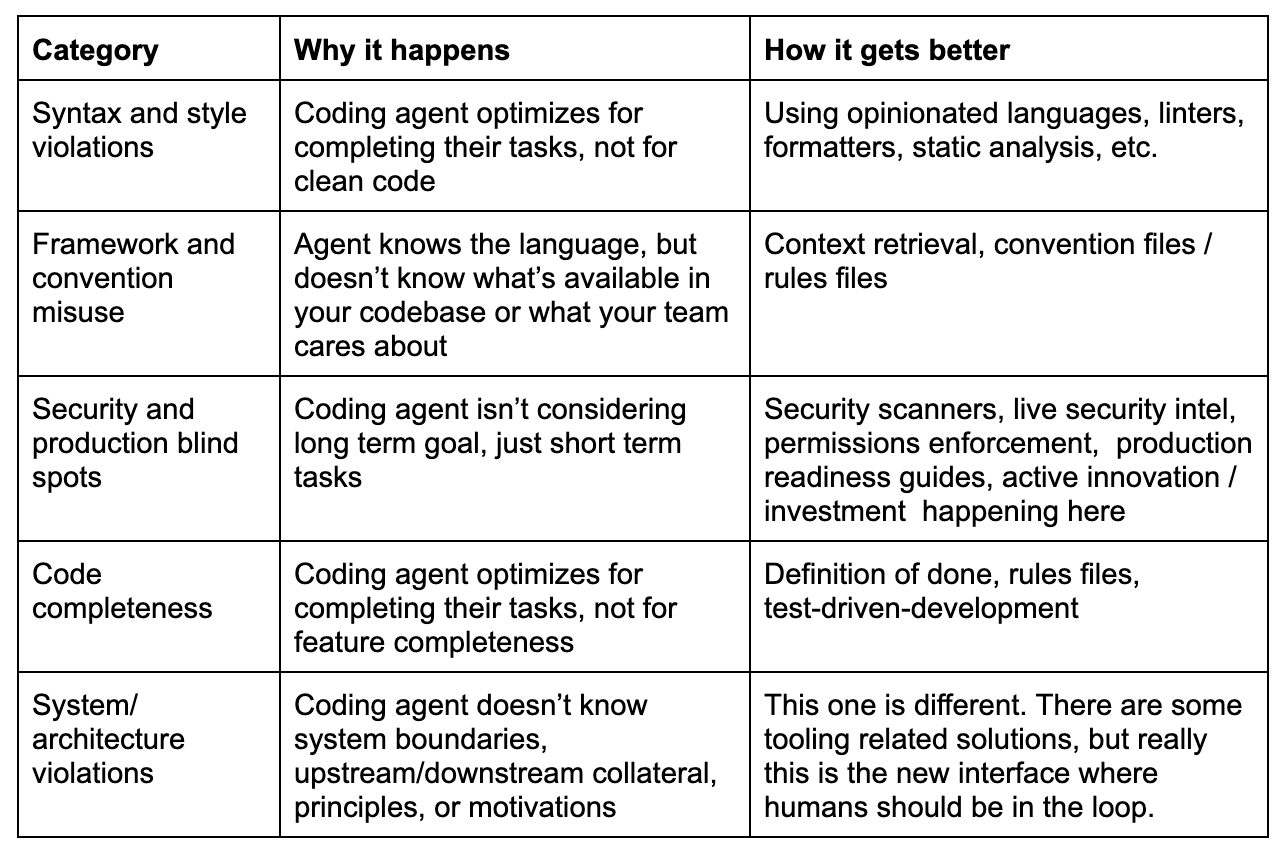

Coding agent mistakes fall into 5 categories:

- Syntax and style violations

- Framework and convention misuse

- Production blindspots

- Code completeness

- Architecture and system-level violations

- 3.5 of them already have workable solutions

- Architecture and system-level mistakes aren’t so much “problems to be solved” as they are the new interface for software development

The categories

It’s easy to look at a list like this and conclude that coding agents aren’t ready and maybe even that they’re too risky to ever be suitable for regulated spaces. There’s more to it than that though. Not all of these mistakes are created equal, in fact some are pretty easy to mitigate. Let’s take a look at the list again, this time organized into categories:

Syntax and style violations:

Imports in the middle of the code Repeated implementations all over the place Useless comments Unused imports and dependencies “Any” is everywhere

Framework and convention misuse

Ignoring reusable project components Creates helper methods then doesn’t use them Creates types for everything (…then doesn’t use them) Using raw/mamework offers ways to do things (i.e. window.location instead of React Router)

Security and Production blindspots

Putting sensitive secrets into client side code Writing raw SQL when the project uses an ORM Using browser alerts in web apps Deleting databases, etc.

Code completeness

Notional or placeholder data Notional or placeholder implementations Creates (and tries to commit) test scripts Comments out problematic stuff with a “come back later” note

System/architecture violations

DB migrations in a class initialization Code that’s responsible for a zillion things so it’s hard to debug or test Changing unrelated code when working on a feature Adds feature flags for everything Redeclaring variables all over the place Complex fallback strategies instead of just… robust code Adds flags, variables, and parameters all over the place Inline objects and functions instead of reusable stuff

Now we can take a look at the different categories of problems:

Syntax and style violations, framework and consuse, and code completeness have reasonable, process-related solutions today. Security and production blind spots have some solutions and are under active development. But architecture is different. Not only do we lack tools for managing at the system-level, but it also isn’t something we can just build a magic tool to solve. It’s where humans in the loop belong.

Why is architecture different?

Why should architecture be treated differently? A style violation is “you put the import in the wrong place.” A convention issue is “you used raw SQL instead of our ORM.” These have right answers, or at least answers that your team has standardized around. Architecture isn’t quite the same. Although questions like “Should this be a separate service or part of the monolith?” “Should we duplicate this data or accept the latency of fetching it?” “How much complexity is worth the flexibility?” are technical questions with technical answers, they require input that is not technical. In other wordduct strategy decisions, risk tolerance decisions, and business constraint decisions.

The problem isn’t that agents make bad architectural decisions. Architecture decisions often aren’t “good” or “bad”, but rather they’re intentionally suited to certain scenarios. The problem is that agents make these decisions silently. When an agent adds a dependency, changes the flow of customer data, or changes how services communicate, it doesn’t announce itself in the diff. It looks like implementation detail. The code gets approved either because of review fatigue or because of speed decisions… the code works and the tests pass. But now you have customer data flowing somewhere that wasn’t approved, or a downstream service that no longer gets fully enriched data from your service, degrading the customer experience.

This is how architectural drift compounds. It’s not always dramatic failures, but there is a buildup of silent decisions which took on a tradeoff or a risk that was not acknowledged e changes faster, and individual developers are each functioning as their own engineering managers, the entire management layer shifts up the stack by one layer of abstraction. Our tools were built for the process pre-shift though. In order to manage architecture effectively, we cannot let architecture decisions get made (sometimes “secretly”) by coding agents. Because they matter… they result in tradeoffs of some kind and this is exactly what humans should be signing off on.

What this means for how we work

Getting the most out of AI-native development requires a few shifts:

- Mitigate the solvable categories. Linters, security scanners, convention files, definition of done—these aren’t optional hygiene anymore, they’re how you keep agents from creating noise.

- Make implicit knowledge explicit. The assumptions your team has built up over time? They need to be documented and enforceable, not just understood.

- Let go of line-by-line code review. You can’t keep up, and it’s the wrong level of abstraction.

The new workflow: define and approve the system design, assign implementation to agents, then verify that implementation matches intent. Humans own the tradeoff decisions. Tools help enforce them in code and verify they stay true as the system evolves.

So…?

Most AI coding agent failures are growing pains that already have growing toolsets for mitigation. But the architecture failures point somewhere different. Not to new tools for the same processes, but to a new process altogether. Teams need to interface with their software architecture and system design. We’re moving up the stack.

This post focused on the pitfalls of coding agents, their categories, and which ones are solvable. I have a lot more to say on this topic (much of my inspiration for gjalla is related), so I’ll stop here, but you can expect a) more tactical posts later which dig into what effective mitigations actually look like in practice, and where tooling gaps still are, and b) updates from us to help your teams maintain visibilityyour AI-generated code.